Wanderers

Exhibition catalogue essay by William Cook. April 2024

On the windswept shore of Strangford Lough, in an old barn converted into a gallery, Colin Watson is showing me his latest paintings. There are nine canvases on these whitewashed walls, and at first glance they don’t seem to have a lot in common. Yet when you look closer, a unifying theme appears. As you scrutinise these subtle pictures, you realise they’re all about departure – vulnerable people on the move, venturing out into the unknown.

A small boy climbs into an open boat, bound for a voyage across a stormy sea. A father helps his daughters over a rocky wall, seeking shelter in the fields beyond. Two isolated children loiter aimlessly on a lonely mountain pass. Now you understand why the title of this show is Wanderers. These strangers are all searching for sanctuary, in perilous places far from home.

Colin is well aware that this subject has become fiercely political. These days migration is rarely off the front pages of the papers – a hot topic on social media, a daily item on the TV news. Looking at these pictures, you can’t help thinking of all those newspaper headlines about ‘illegal’ migrants, TV footage of terrified children in Gaza, or the British government’s latest catchphrase, repeated like an endless mantra: Stop The Boats, Stop The Boats…

Yet to shackle these artworks to current affairs would be to do them a grave disservice. It would reduce them to mere journalism, and there’s much more to them than that. They may remind you of hardships and tragedies here and now, in the Middle East and the English Channel, but they’re actually about something deeper. Eternal and elemental, they aren’t tied to a particular time or place. Rather, they recall that migration has always been a part of life, ever since our ancestors left Africa - roaming the earth for millennia, some of them eventually ending up on the banks of Strangford Lough.

Colin didn’t paint these pictures as a response to the current crisis. He’s an artist, not a satirist – a painter, not a pundit. The ideas that fed these images are actually far older. He’s been living with them for years. That’s the odd thing about art. Sometimes, it becomes a form of prophecy. Paintings can be premonitions, foreseeing the shape of things to come. ‘It’s within us,’ he tells me. ‘There’s something of the wanderer in us all.’

He was born in 1966, into a working-class family in Belfast. His father died of a heart attack seven weeks before Colin was born. Raised by his mother, he loved to draw, at home and then at school. He taught himself about painting by reading art books in his local library. ‘I never spoke to any other painters.’ Finding his own way, in isolation, this autodidactic education preserved his originality, and his integrity. Blissfully unaware of which artists were hip, he was always drawn to Old Masters rather than modern art.

He did a Fine Art degree at the University of Ulster, and spent his summers Interrailing around Europe, visiting the great Continental galleries, in France, Spain and Italy: the Louvre, the Prado, the Uffizi… It was, as he said last time we met, ‘a month of exposure to great painting every year.’

After he left college, art and travel remained intertwined. At the age of 25, he travelled to a remote corner of northern Kenya, to spend a month with the great explorer Sir Wilfred Thesiger and paint his portrait. Thesiger had turned his back on society. He was living in a mud hut with the semi-nomadic Samburu tribe. ‘He had nothing there, nothing at all – no material possessions at all.’ Colin found that frugality exciting. ‘It made a big impact on me.’ Coming from the western world, with its vast surfeit of visual imagery, this lifestyle was a liberation, an escape from information overload. In isolation, with few distractions, he could focus on his painting to the exclusion of all else.

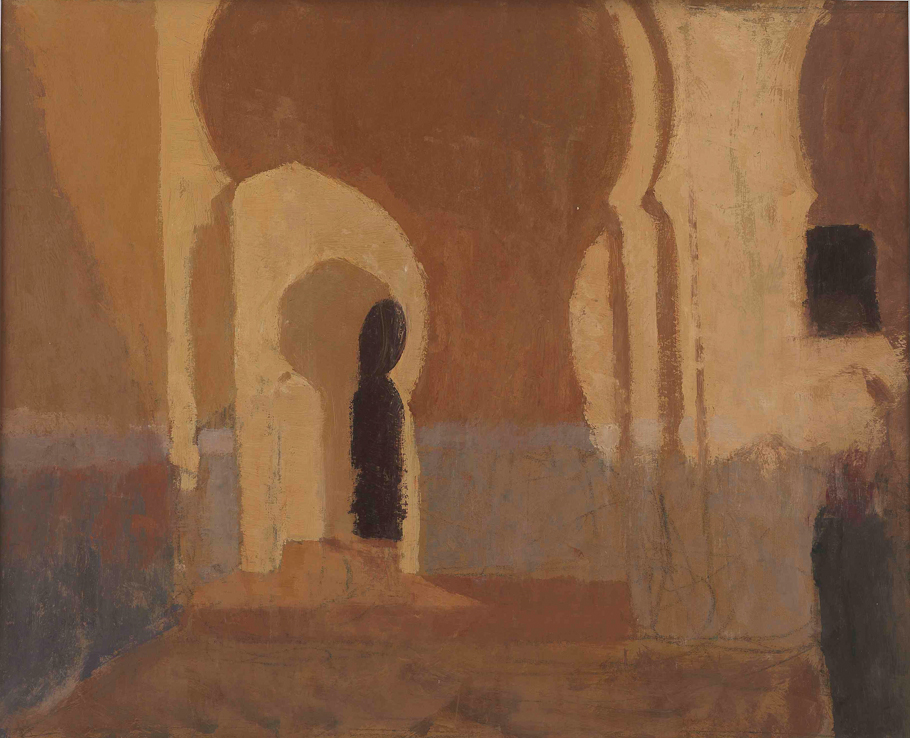

Kenya was an inspiration, but the place that seduced him was Morocco. Its stark landscapes and cryptic cityscapes became the focus for some of his finest paintings, and his deep relationship with that vivid land was cemented when he met his Moroccan wife Karima in Marrakech. They now live in Belfast with their three children, but Morocco remains a constant presence. ‘I escape in painting,’ he says. ‘I roam the Atlas Mountains every day.’

Even in those paintings which aren’t set in any particular locale, some of Morocco filters through. His recent work inhabits a surreal netherworld, a strange melange of North Africa and Northern Ireland, which gives it a dreamlike quality – ostensibly serene, with an underlying aura of unease. ‘That tension brings out something interesting,’ he says. It’s unpredictable.’ It’s not conscious, it’s subconscious. ‘The picture takes control.’

Marriage and fatherhood has changed him. His earlier pictures of Morocco were devoid of people: empty streets, darkened doorways, a lone artist in an unfamiliar land. Nowadays there are people in his paintings, often modelled on his own family. They’re not really portraits, more like archetypes, and like his landscapes there’s an air of unreality about them. In some paintings, there are even a few doppelgangers - two of his daughter, two of him…

Katie Lindsay Gallery, the venue for this exhibition, is a place that shares the magic and mystery of Colin’s paintings. Hidden amid the Drumlin Hills, beside a shallow sea inlet on Strangford Lough (Strangford is an old Norse name, from Strangfjörthr, meaning a fjord with a strong current), this sleepy waterway is reputedly where Saint Patrick arrived in Ireland.

There are dozens of islands in this Lough, plus countless islets (aka pladdies): 365, say the locals, one for each day of the year. Walking along its banks, with only the sound of the wind and the gulls to keep you company, it’s hard to believe you’re only a half hour drive from Belfast.

The Katie Lindsay Gallery is part of the history of this place – a new gallery in an old building, formerly a storehouse for agricultural machinery. For a stranger, an outsider, it’s the last place you’d expect to find a contemporary art gallery, but the more time you spend here, the more it makes sense. A world away from those fashionable high street galleries in Dublin and Belfast, it's intimately connected to the landscape, and the people who’ve fished and farmed here for millennia. I can’t think of a more fitting platform for Colin’s atavistic art…

Now we’re back in Colin’s studio, a cramped upstairs room of his modest, cosy house in Belfast. He’s telling me about his inspirations – not only the Old Masters of the Renaissance, but ancient art from as far afield as Egypt, Persia, India, China, Cambodia and Afghanistan. ‘There’s a strain throughout all great art and all ancient cultures,’ he says. ‘They’re all dealing with the same concerns.’ Like these ancient artworks, his own paintings ask the same fundamental questions, unanswerable questions that nag away at us throughout our lives: As Gauguin put it, in the title of his greatest painting: Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?

On his easel is a study of a picture by Poussin, which he spent three weeks painting in the Louvre. It’s something artists always used to do, but Colin is unusual for still doing it. For him, it’s always been important. Only by scrutinising classic paintings, with a pencil or a paintbrush in your hand, can you really understand them, and learn from them. ‘You’re transported into another realm - you’re learning the essentials of your craft.’

Craft is one of the main things that makes Colin’s paintings so distinctive. When he trained as an artist, in the 1980s, art schools were abandoning the traditional training that had been at the core of art teaching for centuries. Video art was in the ascendant. Figurative painting was on the wane. Unlike a lot of students, Colin didn’t just go with the flow. Instead, he created a classical curriculum of his own. He hired his own life model. He copied Old Masters in museums. These artists taught him a lot, not just about technique but about composition. ‘Structure is the key,’ he says. ‘The most important thing in a painting is the structure. If it doesn’t have structure, it doesn’t have power. It can’t communicate on a profound level. If you don’t have structure, it all falls apart.’ At the time, his focus on draughtsmanship seemed old-fashioned. In fact, he was actually ahead of the curve. Now everyone has a smartphone, film and photography have become commonplace. Immune to digital duplication, figurative painting is now back in vogue.

Not that Colin cares. He’s always ploughed his own furrow, indifferent to the fads and fashions of the art world. Although he’s from the same generation as those trendy, iconoclastic Young British Artists who burst onto the art scene in the 1990s, his work feels far closer to the Renaissance artists he admires. Titian and Poussin would recognise these paintings and respond to them. Does this make him a dull old fuddy duddy? Of course not. As Newton said of his own forebears, he’s standing on the shoulders of giants.

Travel is another thing that marks him out, another thing he shares with artists of the past. Like Turner, or his hero, Delacroix, travel has broadened his palette and saved his art from introspection. His eye is drawn to the wider world, and that’s why his paintings seem so timeless. They could have been painted a hundred years ago, or a hundred years from now.

But ultimately, it’s not his artistic influences or his foreign travels or even his immaculate technique which makes his work stand out. It’s about making the art you want and waiting for the world to find you, and not caring if it never finds you, and finding the courage to carry on painting all the same. He’s been collected by King Charles III, Her Majesty the Queen Consort, the King of Morocco, the Royal Geographical Society, the Ulster Museum, the Arts Council for Northern Ireland and the Moroccan Museum of Modern & Contemporary Art. He’s a Royal Ulster Academician. He’s won numerous awards. But even if his paintings were stacked up in a corner of the studio, with no-one there to see them, they’d still be full of truth and meaning. Going against the grain, against all odds, Colin Watson has found his own voice - and in the end, for any artist, that’s the only thing that really counts.

NOMADS

This painting was inspired by a group of Moroccan nomads whom Colin encountered in an oasis on the edge of the Sahara. He was intrigued by the simplicity of their lives, owning only what they could carry. He was thrilled by the openness, the vastness of the landscape. He was drawn to the darkened doorway of their tent. Who knew what lay within?

‘It started off as an actual group of people, an actual tent and an actual camel,’ he says, but that encounter became a starting point. The painting process distilled it into something more enigmatic, more symbolic.

Colin didn’t want this painting to come across as sentimental or nostalgic. He didn’t want it to appear at all picturesque. ‘You have to go beyond that,’ he says. ‘There has to be an element of tension.’ There’s an ambiguity about these figures. Will they be welcoming or malevolent? We don’t know, but we’re about to find out. That’s what gives Nomads its strength.

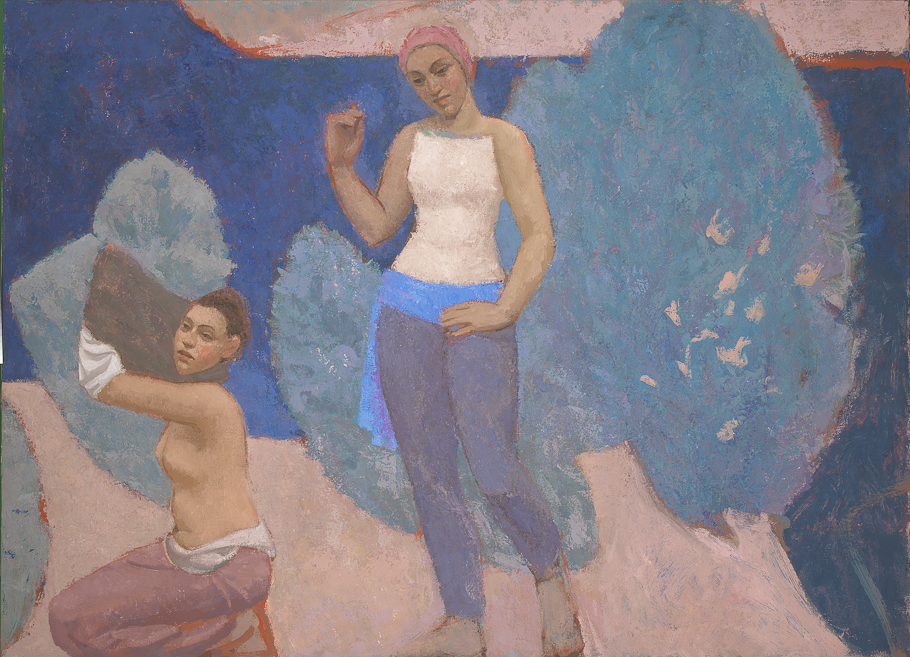

ROCKS, SEA AND WIND

This painting is located on the beach at Essaouira, on the wild west coast of Morocco, down among the rocks beneath the walls of the old city. It’s an intensely atmospheric spot, reeking of romance and menace. The colours are lush, but the mood isn’t calm or peaceful - it’s tumultuous. The sea is rough and restless. There’s nothing between here and America. From this ancient port, African slaves were shipped across the Atlantic, after their long march across the desert. Orson Welles filmed his movie of Othello there.

‘It’s about a woman contemplating the sea,’ says Colin. ‘Is she contemplating a journey that she’s going to make, or has made, or someone else has made? Is she waiting for someone to return? All the possibilities are there.’

CROSSING

This picture was inspired by a woodcut called Landscape With Wandering Family by the Italian Renaissance artist Domenico Campagnola. Campagnola lived 500 years ago, yet the theme of this artwork is still topical. The modern world is full of wandering families, just as it was in the 1500s.

For Renaissance artists like Campagnola, any depiction of a wandering family was synonymous with the Holy Family – Joseph, Mary and the baby Jesus on their flight into Egypt. The Holy Family were refugees, fleeing from Herod’s Massacre of the Innocents. In our irreligious age, this fundamental Christian sympathy for any refugee from persecution has been waylaid.

The idea for Crossing came to Colin several years ago. Lately, it’s become even more relevant, but that was merely happenstance. Rather, it evokes folk memories of forced departures throughout history. Today, people are fleeing across the Mediterranean, just as, once upon a time, here in Ireland, they fled from invading Vikings. ‘It’s not an illustration of an event,’ he says. ‘The picture will live on beyond that and take on different meanings.’

FLIGHT

Flight is very much a companion piece to Crossing. Both pictures stand alone, but they’re even better side by side. One of them depicts a sea crossing, the other depicts a land crossing. Both of them portray a family on a journey that you sense is not of their own choosing. In Crossing, these people must set sail in a small boat. In Flight they must cross a wall.

‘A wall is a great symbol,’ says Colin. ‘It’s a frontier, it’s a borderline.’ But it’s also an escape route. If you can cross this barrier, might there be a better life beyond? Like Crossing, Flight is universal. ‘They’re not of a specific place or time. They can be anywhere at any time.’ They’re about leaving your old life behind and taking a chance on somewhere new.

IT HAPPENS, SOMETIMES, THAT THE WAY IS BEAUTIFUL

This painting takes its title from a picture by Georges Rouault, one of Colin’s favourite artists. All of his family are in the picture, but it’s not a portrait. There are several versions of his daughter, an amalgam of his wife and daughter, and a composite of his two sons. ‘It’s a celebration of tenderness, of calm, of respite from the flight,’ he says. ‘They’re resting on their journey.’ Yet even though it's a peaceful picture, there’s something disconcerting about it, something you can’t quite put your finger on.

After Colin started painting this picture, this verdant terrain, in the foothills of the Atlas Mountains, not far from Marrakech, was ravaged by a violent earthquake. Thousands of people died. ‘The epicentre of the earthquake would have been just over that ridge,’ he says, pointing at the picture. ‘There’s a good chance that village was wiped out.’

There’s no inkling of that disaster in this picture, yet somehow, like a distant rumble, a faint vibration, a sense of impending doom seeps through. Happiness is fragile – transient and fleeting. You know it cannot last. Even in such a tranquil spot, catastrophe is never far away.

Colin was in Marrakech when the earthquake struck. He was planning a day trip to this place the day before. Did that experience change this picture? Now you know what happened here, does it seem different to you? Or maybe, like me, you already had a vague sense of that before?

MOUNTAIN ROAD

This picture depicts the Tizi n’Tichka pass, which runs across the backbone of the Atlas Mountains, linking the Moroccan cities of Marrakech to the North, and Ourzazate, to the South. ‘I’ve been travelling over this pass since the 1980s,’ says Colin. ‘It’s probably my favourite route in Morocco.’

It’s a rugged landscape with a harsh climate, and the lifestyle is traditional. Donkeys are still an important mode of transport. During the winter, when it snows, this road is closed. The only way across it is on foot.

‘Here, people are living lives that haven’t changed in millennia,’ says Colin. ‘The rocks are ancient, and the distances are epic.’ The scene is deliberately ambiguous. Who are these people? What are they doing here? There’s no way of telling. It’s the sort of situation you often encounter on a long journey, anonymous strangers by the roadside, neither friend nor foe.

BOY RESTING ON SAND

Like Rocks, Sea and Wind, this picture is set on the beach at Essaouira. ‘Because they’re in traditional Moroccan dress, it’s obviously an Islamic beach. There are no westerners there.’ However the specific location isn’t particularly important. ‘It’s as much about distance and space as anything,’ says Colin. ‘The sea and the sand are as important as he is.’

MEETING PLACE

‘It’s an inhospitable desert landscape with only traces of human habitation,’ says Colin, of this painting. ‘A broken wall, an ancient track, a distant ribbon of cultivated land.’ An adolescent girl clutches a toddler to her chest. Is this her sister or her daughter? Is this toddler awake or sleeping, alive or dead?

As Colin says, there’s a dramatic contrast between the intimacy of this human image and the vast, desolate terrain that engulfs and overwhelms it. It’s both tender and disquieting. Like all his finest paintings, it provides no answers, only questions. There are no correct solutions. The meaning is up to you.

PATH TO THE MOUNTAINS

‘It’s based on a scene in the Mourne Mountains, so it’s very much Northern Ireland,’ says Colin. ‘It’s one of my children, but it’s not a portrait.’ He took his kids there for a day out, and that’s when the image came to him. ‘There’s a picture in here,’ he thought. ‘What it is, I don’t know.’ But there was something about the scene that moved him. He’s been working on it ever since, finding out what figures should be in it and what they should be doing. At first his daughter was in it too, but then she disappeared.

It’s a happy picture, but there’s an undercurrent of foreboding. It’s a sunny day but the hills above are dark. Is the weather about to turn colder? Is nightfall far away? ‘He’s not prepared for the journey,’ says Colin, and the conversation turns again to wandering. Wherever he finds himself, in his own mind he’s always roaming. These pictures are records of his travels - not so much to distant lands, but to the landscapes inside his head.

William Cook is an author and journalist who writes about art and culture. He has won several awards for his journalism, including the Johann Strauss Gold Medal for his reporting from Vienna.

ENDS